Wendell Castle once commented that often not enough time is spent designing a piece. The same can be said of researching a piece.

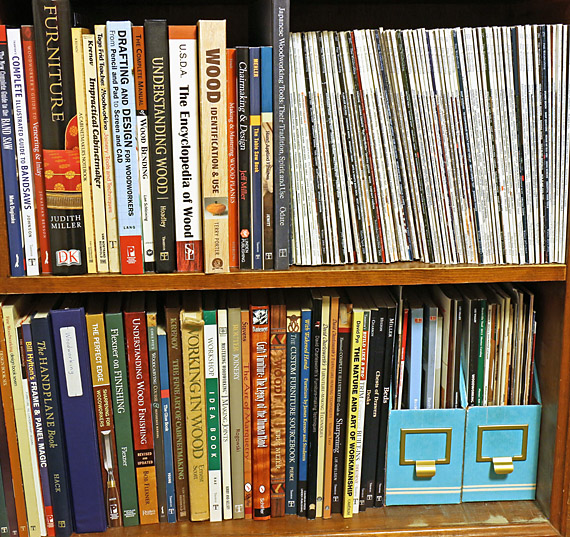

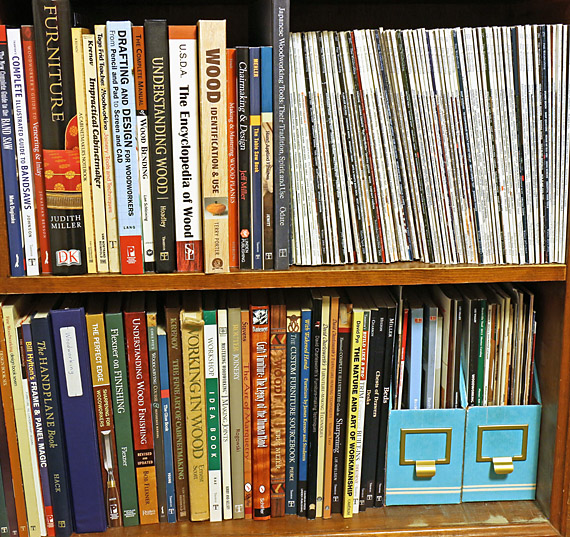

Unless you have previously executed something very similar, neglecting adequate research can lead to a lot of wasted effort building a disappointment. The research phase of a project should be enjoyable as the possibilities unfold and your woodworking knowledge expands.

Here are four categories that require attention. To illustrate the breadth of research sometimes required, I have used the example of a wedding wine box that I recently completed. This piece had very special significance and I wanted to approach it fully prepared.

1. Function

Almost all woodwork is functional. You do not want the beauty of a piece to belie an inability to do its job. Think of it this way: making a bat requires more than understanding wood and turning; you have to understand baseball.

I researched all the dimensions of the wide variety of standard Bordeaux and burgundy bottles to design a versatile cradle that would accommodate a range of bottles. I also had to learn about how wine should be stored long term.

2. Materials

This is not an area for guessing or shortcuts. Processes that are routine in one wood can be fraught with surprises in another species. What’s more, nearly every project involves several non-wood materials that woodworkers have to understand.

A few boards of gorgeous curly ovangkol (shedua) caught my eye. I had not worked with this species before, so I needed to explore the range of figure it had to offer to be able to choose top quality stock. I looked at objective data on its physical properties and movement characteristics. Most important, I did some practice sawing, chiseling, and planing to appreciate its working properties. It was surprisingly incompressible and somewhat brittle so there was very little margin for error in the joinery.

I considered lots of options for secondary woods, settling on wenge and a billet of killer figured redheart big-leaf maple. I trialed finishes, tested glues for special situations, and also researched leathers.

Then there’s hardware. Ugh. There are always oodles of options here, though often I am not happy with any of them and end up modifying or at least fine-tuning the best available materials.

3. Constructions

Almost every piece I make involves at least one modified or non-standard construction technique. It really helps to consider solutions that other woodworkers have used, though it is important to use sound principles and experience to distinguish good information from bad.

If you never venture from the conventional, you miss out on a lot of fun in woodworking, but you must build right, so do your research.

In this project, I could not find a satisfactory solution for a cradle that would snugly hold a range of wine bottle sizes. What I worked out is no marvel of engineering but I did have to sit at the drawing board for a long time scratching my head, and make mock ups, before settling on a solution.

4. Techniques and Tools

Similarly, every project is an opportunity to develop as a woodworker by learning new techniques and reinforcing skills that you have used before. A good woodworker should never be too proud to practice even those skills that were acquired some time ago.

And yes, there is also the excuse – oops I mean perfectly valid reason – to buy a new tool, which, by the way, has to be studied and tuned. In this project, because I did not do enough research, I needed the excellent Lie-Nielsen drawer lock chisels to bail me out, as mentioned in an earlier post.

In summary, researching function, materials, constructions, and techniques/tools is smart woodworking. Note to self: don’t cheat on your homework.