Sharpening tools should integrate into a logical system. Here is how and why I have revamped my system to use diamond stones as the workhorses.

The tools

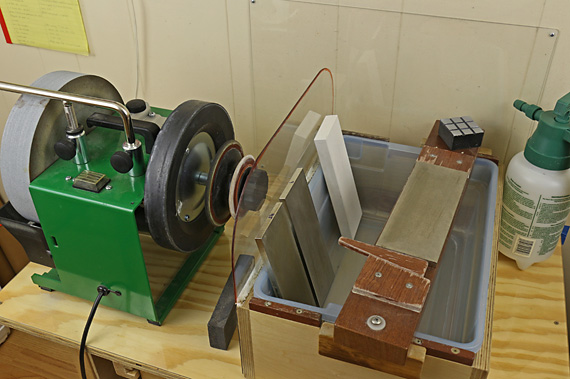

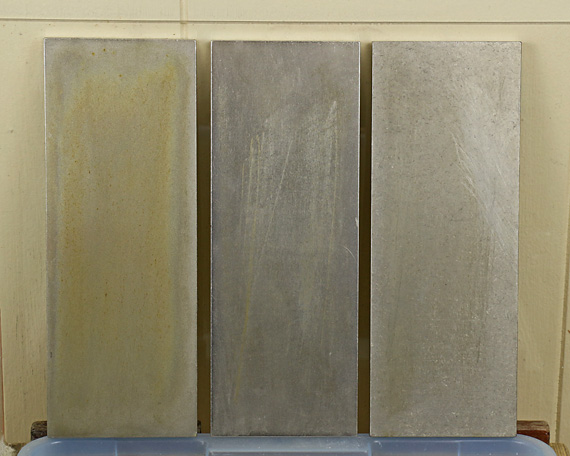

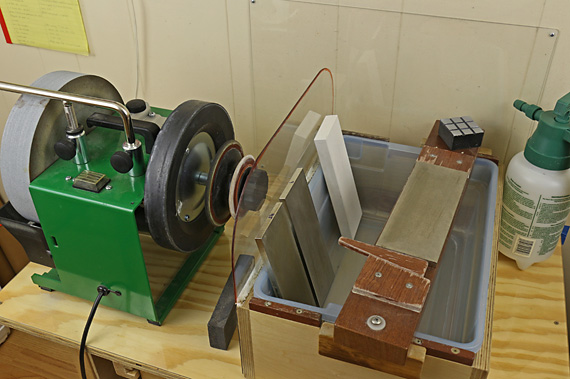

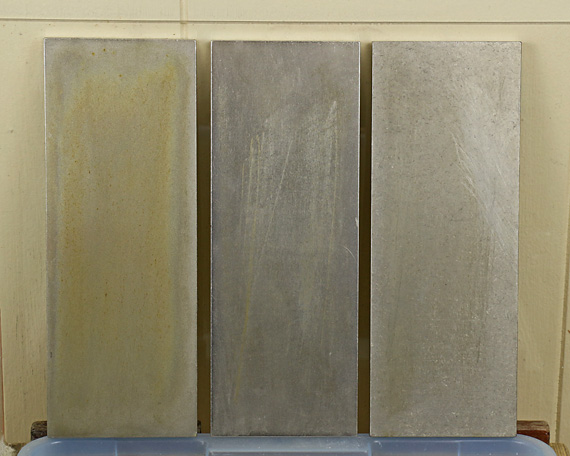

The system uses three DMT Dia-Sharp 8″ x 3″ continuous surface diamond stones, a very fine ceramic finishing stone (about 1/2µ), and the Tormek 10″ grinding wheel. The diamond stones are: 45µ (325 mesh), 9µ (1200 mesh), and 3µ (8000 mesh).

At this size, these diamond stones fit in the same holding device as most waterstones and provide enough length to accommodate a honing guide, if desired. I measured the flatness of each using a Starrett straightedge to be better than 0.0005″ (half a thou) over the whole surface.

Diamond stones cut wonderfully fast, require minimal maintenance, and last a long time. Compared with coarse and medium waterstones, they create less mess, and minimize the chance of transferring grit from stone to stone via the blade or a honing guide.

The processes

A tool makes only infrequent trips to the Tormek to reconstruct the primary bevel. The 10″-diameter grinding wheel creates a mild hollow. I usually grind barely out to the edge or just short of it. Next, I clean up the primary bevel with the 9µ/1200 diamond stone by creating small flats on both ends of the hollow, and sometimes use it to start the secondary bevel (e.g. to start a slight camber). Then I use the 3µ/8000 diamond stone to form the secondary bevel, and finally, the 1/2µ ceramic stone with my diamond nagura to bring it to an exquisite edge.

The 45µ/325 diamond stone supplements the Tormek, such as for forming the primary bevel on certain awkward or small tools, or for adjusting a large camber.

For resharpening on the secondary bevel, which is what we are doing most of the time, I use the finest stone I can, based on how dull the edge is. The idea is to strike an efficient balance that avoids spending too much time on the finer stones while minimizing the depth of the initial scratches that later must be removed.

Thus, if just a bit of touch up is needed, the ceramic finishing stone alone may suffice. More often, I’ll start with the 8K diamond, or, if the edge is quite dull, the 1200 diamond, and work down from there.

When working on the secondary bevel, it is important to use a light touch on the diamond stones. I back off any remaining burr or use the “ruler trick” only on the ceramic finishing stone to preserve the polish on the back of the tool.

The key to this system is that diamond stones comprise the literally central position in the process where their speed and responsiveness quickly get the edge ready for the “money” stone – the finest stone.

For the most critical edges, such as a preparing a smoothing plane blade for the finest work, I finish off the edge by stropping it on leather charged with diamond paste down to 1/8µ, perhaps just to make me feel better.

Though these are my usual processes, the great speed of the diamond stones makes it easy to improvise steps to accommodate different situations such as edge nicks, different steels, edge reshaping, etc.

Why these three grits of diamond stones?

I chose these stones (45µ, 9µ, and 3µ) empirically by experimenting with small stones, basing my judgments on sharpening efficiency and edge performance. The key point is that this set of stones works well for me as a system.

Factors in sharpening stone performance are numerous and complex; grit size is only one of them. A diamond stone performs quite differently than a waterstone of the same nominal grit, so using the same numbers for choosing a series of each type of stone would make little sense. Trial and observation work best.

This set of stones yields for me an efficient balance between minimizing the number of stones and minimizing time. I can maintain proper edge geometry, and get very good responsiveness and feel of the steel on the stones at each stage of sharpening. Overall, the increments in grits seem just about right.

Such choices are certainly subject to personal preferences. For example, many woodworkers may prefer the 8K diamond to be the final stone and finish off the edge with some stropping, or prefer to use larger or smaller increments in grit size.