Fellow craftspeople, shop dwellers, makers of things, maybe you can relate to this.

Tuesday afternoon was fun time at 13 years old. School let out at noon, and not long after, my friend and I would meet up at our fishing stream to catch sunfish, crappies, and perch. There was little art to it, just basic tackle, night crawlers, and red and white plastic bobbers. It was a decent way to spend youthful time.

My pal and I intermittently conjured ourselves to be real fishermen with serious skills, and more exotically, fly fishermen. We even earnestly tied a fair number of flies using some authentic materials, but with no real intent (or ability) to put them to use.

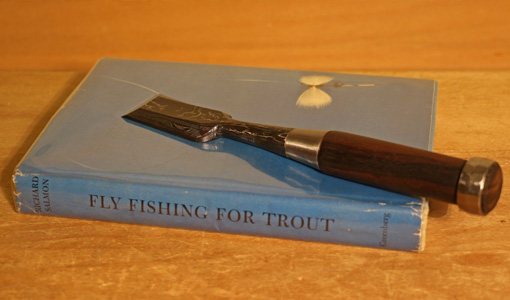

However, this kid stuff led me to borrow a book from the library that resonated so deeply with me that I never forgot it. A few years ago, while reminiscing about this, I used the internet along with a vague recollection of an oddity about the author’s name to locate a copy of Fly Fishing For Trout, by Richard Salmon, published in 1952.

As a young teen, it was my first encounter with the intricacies of how someone does something truly well, along with the driving passion. It stood in inspirational contrast to my naive efforts at fishing. I marveled at the author’s melding of scientific knowledge, meticulous attention to detail, and deep experience into superbly expert fishing skills. He described details of fish anatomy and physiology, subtleties of stream conditions, and nuances of equipment, all in the context of studied experience. This was serious stuff, even intimidating.

Perusing my copy now, I also appreciate the author’s peaceful, trusting tenor, and, nostalgically, the lack of today’s widespread ostentation.

I sensed then – and understand now – that this book reflected a deep desire in me – to simply do something very well. It is a joy for the soul to unboundedly immerse the mind, heart and hand in a meaningful pursuit.

No, I never took up fly fishing, but it sure is good to be in the woodshop.

From Richard Salmon, page 81: “For in fishing as in anything else, you must, if you are going to get results, have your heart in your work. The more joyous I am on a stream, the more enthusiastic, the heavier my creel. But to be happy and enthusiastic, I must believe in the fishing tools my hands control – must believe that I can work naturally, carefully, and well.”