4. Interpret the information and use it.

“Yes, I am asking you to fuss with wood.”

-James Krenov, from The Fine Art of Cabinetmaking

In this final installment on the topic of moisture meters, I will broaden the discussion to the management of wood that has been dried and brought into the shop, from wherever you have obtained it, because it still needs attention before it is ready to be used in a project. A moisture meter can help here.

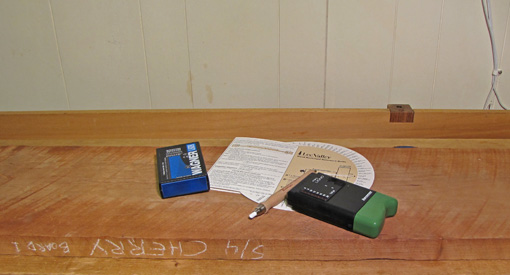

When a new board comes into the shop, I write the date and moisture content (MC) on it. I refer to the back of the Lee Valley Wood Movement Reference Guide to know the equilibrium MC for the ambient relative humidity (RH) indicated on my shop hygrometer. (Temperature is a negligible factor for practical purposes.) The FPL Wood Handbook has the same information. I try to keep the RH within about 40 – 65%, winter to summer, with the use of a humidifier and dehumidifier, as needed.

Unless I am lucky, the wood has some adjusting to do. Therefore, I store it so air can circulate on all sides of each board by storing it horizontally on a rack and stickering it, or leaning it vertically against something. Sometimes I will do an initial light skim planing to get a peek past the rough surface, and to facilitate measurements with the pinless meter.

Then I keep an eye on the wood, checking the MC in a few days to see if it is moving. Depending on the initial MC, species, and thickness, I look for the MC to level off over the next few weeks. The wood is then ready for the first dressing.

Another approach is to look for when the MC of the new wood matches that of wood of the same species that has been in the shop for a long time. Beware, however, of the density issue with pinless meters that was discussed in the previous post. Also beware of the possibility of a moisture gradient through the thickness of the wood, especially in thick stock.

I usually use the pinless meter for this because it is faster and doesn’t make holes in the wood. However, if surface or density issues seem to be confusing, or if the stock is thick and I want to look for a moisture gradient, I will turn to the pin meter for additional information. If I could own only one? Pinless, probably. No holes.

Could this be done without a moisture meter? Sure. Patience and experience will work. Even quick monitoring with a straight edge on flatsawn boards will be informative. I like the convenience and greater reliability offered by the meters to help avert disappointments.

Unless it is very tame straight-grained wood and the final thickness is only slightly reduced from the initial state, I usually dress rough stock in two stages, even after it has reached uniform equilibrium MC. For example, to get a finished 5/8″ from a rough 4/4, I will first joint and thickness down to 3/4″, taking approximately equal thicknesses off each side of the board.

I watch the wood. Did the initial jointing stay flat and true? Did new a twist arise, or maybe a slight bow? These surprises can come about from internal tension releasing when some thickness is removed. Odd grain and case hardening are among the possible causes. These issues will usually manifest their effects quickly, sometimes immediately.

Then I take the wood down to final thickness, removing any slight distortions. If the distortions are large, or reappear, I usually find another board.

Resawing is another matter, discussed here, but requires knowledgeable observation and understanding casehardening to avoid disappointments.

Understand the wood. Watch the wood. A moisture meter can help.