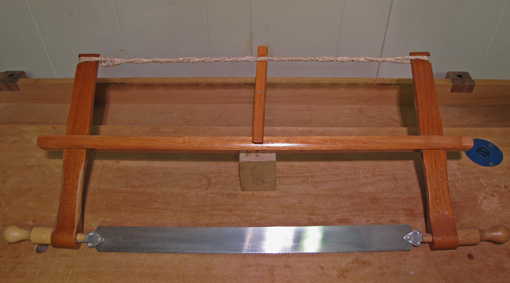

This coping saw frame is an old one made by Eclipse in England. The handle, threaded stem, proximal blade anchor, and the yellow tabs are transplants from an otherwise poorly designed $8 Irwin saw. The handle’s rounded triangular cross section and comfortable grippy material make it less fatiguing to use than the wooden original.

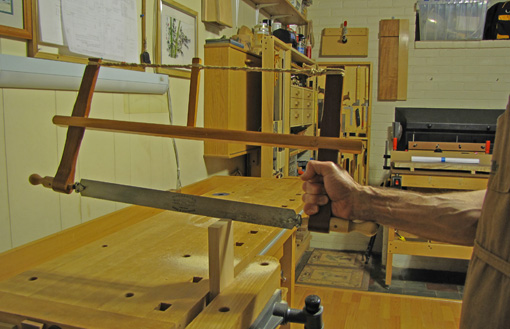

Small frame-type saws like these lack the robust rigidity of their larger cousins and thus perform better cutting on the pull stroke, which also happens to be more natural and efficient when it is used vertically.

I like Olson CP304 blades for general work (.020″ thick, .125″ wide, 15 tpi). The CP301 blades are slimmer (.018″ thick, .094″ wide, 18 tpi skip tooth) and may fit into the kerf of some dovetail saws when used for removing waste, though the total set of these blades varies from about .002″ to .008″ in the ones I measured. CP307 (32 tpi) are handy for the inevitable metal cutting that woodworkers do.

In addition to “serious” work, the coping saw is great for very young kids who tend to dig in and stall with heavier handsaws. The coping saw seems to avoid this because the blade is under steady tension, helped along by the pull stroke. The blades, of course, are inexpensive.

Clamp the wood firmly for the little woodworker, who should use two hands on the saw. You will be the only one who cares if the cut is straight. Even at younger than four years old, my son and daughter played in the shop with me, sawing little wood pieces, building little things, and making big memories.

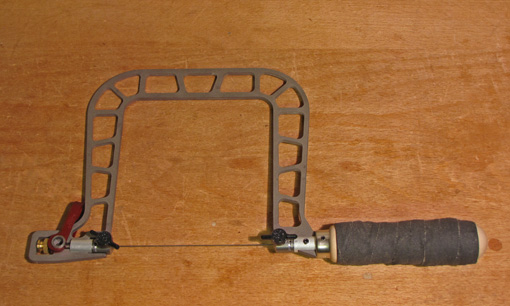

Knew Concepts takes coping and fret saws to vastly higher levels. I have an earlier model 5″ titanium frame fret saw. This style is currently available in aluminum, in addition to the newer “bird cage” titanium model. They also make a similar coping saw.

These saws are amazingly light and rigid, plus offer a convenient cam lever tensioning mechanism and indexed blade tilt adjustment.

This saw is excellent for inlay work using #2/0 blades (28 tpi skip). Again, the pull stroke setup is best. I wrapped the handle in black friction tape.

It is by far the best saw I have used to remove dovetail waste. You can get very close to the baseline using a single cut. This makes chiseling the remaining waste faster and, with less push back of the chisel, more accurate. The fret saw blade easily fits into the kerf made by most dovetail saws, and can be redirected sideways within one stroke.

After experimenting, I found #3 blades (Pegas brand) to be the best for this task (.0118″ thick, .038″ wide, 19 tpi skip) – faster, narrower, and cleaner than the #5 (.0145″ thick, .043″ wide, 16.5 tpi skip).

Knew Concepts saws are examples of tools for which we might otherwise have complacently accepted the limits of the standard designs.

Next: miscellaneous saws that solve problems.