Even skillfully made, sound joinery may have occasional small gaps. These will probably summon little or no notice from people who view and appreciate the piece, but nonetheless disturb the vanity (oops, I mean genuine pride in craftsmanship) of the maker. The wood itself may also have small defects. As long as these imperfections are few and small they are not likely to disrupt the overall aesthetic impact of the work. Still, we want them to disappear.

This discussion deals with fine gaps, not craters, canyons, dents, or seriously mashed wood fibers. Keep in mind too, that you’re in trouble if you have to rely on fillers because your joinery is just plain sloppy, especially if its structural strength is compromised by poor technique.

Let’s look at various situations. (Caution: purists and fantasy woodworkers should stop reading here.) Where end grain and side grain surfaces adjoin, such as in dovetails, fillers can do a good job of hiding small gaps. The same is true where side grain surface meet along an irregular border, such as in artistic inlay. However, even small amounts of filler can be noticeable where the eye expects an unbroken linear border between side grain surfaces, especially if the grain directions are perpendicular to each other such as in a flush-fit tenon shoulder. It is much better to detect and correct that sort of problem after dry fitting. Finally, some problems are probably best just left alone.

Here are some materials that have worked well for me. Readers, no doubt you have your favorites.

Timbermate, made in Australia, is the best premade filler I have found. It is ready to use, dries fast without shrinking, and takes stains and colorants in its wet or dry state. It is a water-based formula available in 13 colors plus a white tint base. An 8-ounce container is probably a lifetime supply for me. No worries, mate.

Of course, there is also the old sanding dust mixture routine. Most wood glues, such as Titebond III, make a good base. Titebond No-Run No-Drip produces a thick, fast-drying paste using less dust, and can make a lighter color paste. Zinsser Seal Coat dewaxed blond shellac makes a thin paste that dries very quickly. I find epoxy is too messy, and CA glues are quick but less controllable. Experiment.

Sand up a small pile of dust from a piece of scrap and mix in some glue or shellac. Use a file or fine rasp for coarser dust or if the possibility of grit in the paste is a problem. The key is to regulate the color and texture of the paste based on the glue or shellac, the tool used and thus the fineness of the dust, the species of wood used to produce the dust (which may not be the same as the project wood), the finish to be applied, and the anticipated long-term change in the color of the project wood.

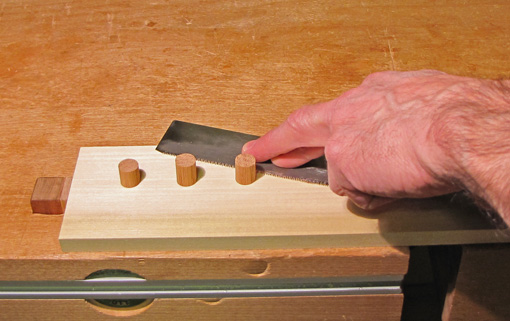

For application tools, try toothpicks, tapered craft sticks, bamboo skewers, and so forth. I usually break the stick to produce a sharper end. Wax modeler’s spatulas, available from Lee Valley, are nice for precise work, though they superficially blacken Timbermate with continued contact. For removing excess paste and leveling the surface, I like to use a mini card scraper.

Wax filler sticks, available in lots of shades, are useful for quick touch up work after the finish has been applied. They have the advantage of color matching to finished work, but keep in mind that many woods darken over time.

I guess we can feel better recognizing that there is some art to covering up imperfections.