Tip #2: Engage and stabilize your core.

“Core” muscles refer to the abdominals, obliques, hip flexors, spinal stabilizers, and the gluteus muscles. Strong, balanced, and activated core muscles allow the limbs to perform properly. Core involvement is the source of much of the precision and power of a tennis player’s swing, a fighter’s punch, and a sawyer’s stroke. Watch Chicago Bears linebacker Brian Urlacher demolish a ball carrier, or Boston Red Sox little guy Dustin Pedroia belt a ball over the fence, and you’re seeing core strength in action.

Pick up the saw, place one foot forward, and use your core muscles, especially the glutes, to find a balanced, stable stance. From there, the arm can operate with precision, intent, and strength. A stable core does not mean an immobile core, rather it is a controlled positioning and movement of the trunk. If the trunk is unstable, the arm flails.

Do not fall into the saw stroke, move into it. Maintain balance throughout the stroke. Do not use the bench or the work piece to prop up your body. A partial exception is when using a handsaw with a low saw horse or bench. Even in that situation, the non-sawing hand is really just an aid to the core musculature. You should not be falling on that hand with each stroke. Again, move into the stroke with intent and control, do not flail into it. You can still use your body weight for power, but in control using the core.

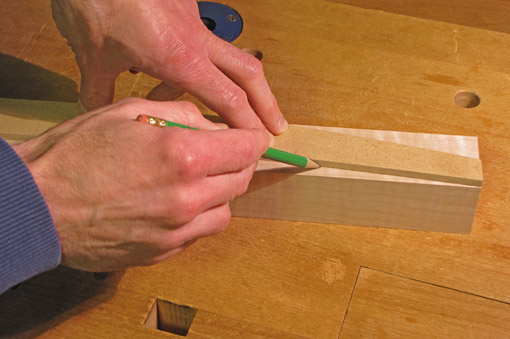

It was difficult to take photos for this post. I set the timer and quickly moved into position with the saw but I could only approximately convey the general ideas.

Whew, look at this guy. Bad news:

And this guy. Ouch. He won’t last a day in the shop.

In addition to sawing precision and strength, you will also have shop endurance. Woodworkers often complain of low back soreness after a day in the shop, especially with tasks such as sawing joinery and sharpening. The way to avoid this is to use a balanced stance and active glutes to take the excess effort away from the lower back muscles. This applies to machine work too, such as precision sawing at the bandsaw.

Try this: pick up the saw, channel your inner Bruce Lee, and concentrate much more on your stance and core activation – stable, not stiff; intent, not mushy. You may surprise yourself to find following the line is easier and more natural than if you think just about your arm and the saw, forgetting about the all-important core. Be Bruce grabbing the cobra.

The core matters in sawing. I leave it to you to do the homework.