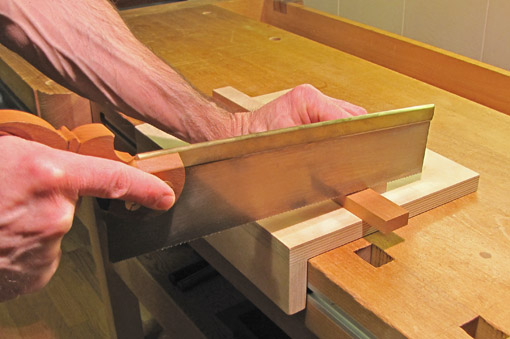

A bench hook is a handy workbench accessory, mostly for crosscutting small parts. This version works well with both Western push saws and Japanese pull saws.

I try to keep workshop jigs and fixtures as simple as possible (“but no simpler,” per Einstein) and this one is no exception. It is constructed from plywood and maple, using simple glue and biscuit joints. The base is 12″ wide by 9″ deep with a 13/16″ high by 1″ wide maple fence at the middle and a 2″ wide cleat for hooking the bench. It could just as well be screwed together. The fence is shortened on the right side for a right-handed woodworker.

For use with push-stroke saws, the jig is simply placed on the bench top with the cleat catching the front edge of the bench. The work is held in place by hand with forward pressure against the front side of the fence. Aided by the sawing pressure, this also holds the bench hook itself in place.

For use with pull-stroke saws, the work is placed against the back side of the fence. Since the sawing pressure is toward the user, it will pull the work against the fence but will also tend to displace the bench hook. This is not a problem for light work because I can lean forward the heel of my left hand against the fence to stabilize the bench hook while gripping the work piece against the far side of the fence with the rest of my hand. For more substantial pieces it is better to secure the bench hook in the front vise of the workbench.

I do not generally use the end of the fence as a guide for the saw, and do not use a fence with 90̊ or 45̊ kerfs, though some may prefer these options. I work to a line marked on the wood and just eyeball noncritical cuts.

This bench hook is unscarred because it is new, replacing one of the same design that got too beat up. As with so many tools in woodworking, it takes a long time and many situations to get a real sense of the effectiveness and versatility of shop jigs. This design has served well over many years so I continued it for the new one, only making it slightly larger.

The bench hook comes in handy for more than sawing. All sorts of work on very small pieces, such as paring and chopping seems to get done on the front side, against the fence. I do not shoot on it; I use a shooting board for that.

Once again, simple and proven effective.