Following up on the problem posed in the previous post, here is how I managed this board. Most important, I proceeded step by step, watching the wood. The procedure below may seem complicated, but it really is simply a matter of understanding wood and using good sense.

Before doing anything else, it pays to perform the casehardening test. This will require cutting an inch of length off the end of the board and sawing out the core of the offcut to create a long “U” shape. Please refer to the method described in an earlier post. This board, like most thick stock, had some casehardening stress in it.

Starting with rough stock nearly 1 ½” thick and about 9″ wide, the final thickness at the center of the 25″ length will be just under 11/16″ and, at the outer ends, just under 1 3/16″, for a curve depth of ½”.

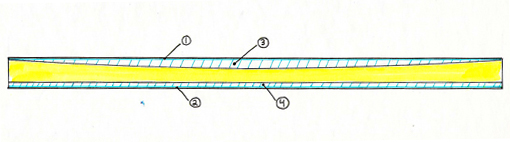

The diagram is only roughly to scale. It really is intended to give a qualitative sense of how the board was managed. The numbers in the diagram refer to the steps discussed below.

1. I investigated the board by skimming the faces on the jointer just enough to decide if the board will look nice and to choose the show face which will be the curved face on the outside of the cabinet.

2. The opposite (inside) face was hit-or-miss jointed enough to establish flatness. This leaves some rough areas remaining, but enough of the face is smooth and flat to serve as a reference for marking out the curve. At this point, there is less than 1 3/8″ of thickness remaining. I also did a light pass through the thickness planer (with the flat side down, of course) to get a better look at the show side and to estimate how much thickness would be surviving.

3. I sawed the curve with the bandsaw. The layout line was drawn almost up to the surface of the board at the ends. (I had left an inch or so of extra length at each end.) I sawed away from the line, guided by a second line drawn less than 1/16″ away from the original line. This allows for clean up later.

Because substantial thickness was now removed from one side of the board, it promptly distorted so the flat side wasn’t flat anymore.

4. I then removed wood from the inside face which neutralized some of the distortion and re-established the flatness of this face. I did this mostly by hand planing which gave me a chance to keep an eye on things as I went along.

I then cleaned up and refined the curved face, rechecking the flat face as I went along and making minor corrections as needed. At this stage only small quantities of wood were being removed so only minimal correction was required.

The board now sits on stickers as it awaits its role in the construction of the cabinet.

Despite all of this forethought and care, it still helps to have some luck with wood, but it’s not so wicked after all.

I wonder if there is another way to flatten a board like this. I’ve straightened greenwood by tying it to something. Steam bending can practically twist wood into knots. You might be able use steam or just water to soften the wood, then put it on a flat surface with enough weight on top to flatten it to the surface. Leave it until it dries. That may offend some woodworkers sensibilities, but if it is the only way to save an expensive potato chip why not try it.

I don’t know. This board worked out OK with what I did. I guess if there’s a problem board with no thickness left to spare, your method might work.

Rob