And the winners are . . . end mills! Here’s why.

I do most of my mortising with my trusty Elu 3338 plunge router, currently available as the DeWalt 625, in conjunction with various jigs, most involving a template guide riding in a slot. In the past, I used solid carbide upcut spiral router bits with generally good results, though I often encountered two problems.

First, 1/4″ and 3/8″ spiral bits are usually sold with cutting lengths of 1″ and 1 1/4″, respectively. I often want to make mortises deeper than that. Second, 1/4″ and 5/16″ diameter bits, especially some rare, long-length, HSS versions, will sometimes vibrate in the cut and produce steps on the mortise walls. Even a 3/8″ bit may be made with a surprisingly thin web at the core of the spiral which can cause the bit to flutter when cutting dense woods.

I like standard, four-flute, center-cutting, single end mills in uncoated solid carbide with a plain shank and a 30-degree helix. These are available in longer overall lengths with longer cutting lengths than router bits, thus allowing deeper mortising. I find the cutting action of these four-flute end mills has less vibration and is smoother and more balanced than that of router bits. This results in cleaner mortises. Furthermore, these end mills are generally less expensive than comparable router bits.

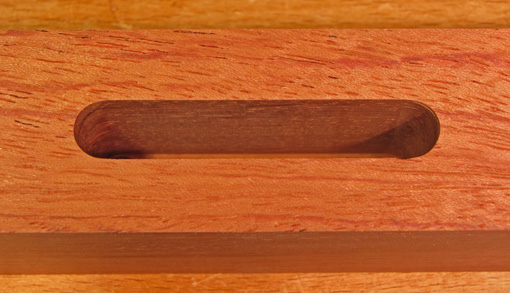

The photo at top shows, from left to right, 1/4″ and 3/8″ upcut, solid carbide router bits, and 1/4″ and 3/8″ end mills. The 3/8″ end mill is 4″ long with a cutting length of 1 3/4″. The router bits tend to strain in the cut whereas the end mills purr like a sports car. The mortise pictured below is 3/8″ wide, 2 3/8″ long, 1 1/2″ deep and was cut in bubinga, a dense wood, with the bit at the right in the top photo. The walls are very clean and true.

The disadvantage of an end mill is that the cutting diameter equals the shank diameter. Therefore, I usually mortise with a 1/4″ or 3/8″ end mill using a router collet of the same size for each. A 5/16″ end mill can be used with a shank adapter though I prefer to avoid these adapters. When mortising with end mills, just as with router bits, it is good practice to cut the mortise in small depth increments, always listening to and feeling the feedback from the machine and adjusting your technique accordingly.

Sources for end mills are industrial supply houses such as MSC, Enco, McMaster-Carr, and Grizzly. It will take a while to go through their catalog algorithms or directly study their catalog pages but these are good ways to learn about this type of tooling. The upgrade has been worth it for me.

I thought end mills weren’t rated for the same rotational speed as router bits. Do you slow your router down to use these?

Hi Dennis,

I run these bits at 20,000 rpm. Some cautions that I employ are: chuck at least 1″ of the 3/8″ bit into a top quality collet such as in the DW625, cut the mortise in small depth increments, clear chips frequently with a vacuum, do not mortise deeper than the flute length, use a steady, reliable jig setup, and be alert to signs of strain from the router. For example, it took at least 8 or 9 passes to make the mortise in the picture. I get no burning or chip congestion.

I have not been able to find industry information on maximum RPM/SFM for this type of bit for mortising in wood, though there is, of course, much pertaining to machining metals. The core of these bits is more substantial than that of the same diameter spiral router bits. The 3/8″ mill is made by Atrax; the 1/4″ is from Grizzly.

I can only report what works for me in my shop with my tools and techniques. Readers must, of course, decide for themselves how to work in their shops.

Dennis, thank you for your comment; it helped me clarify what I was trying to present.

Rob

Rob,

I have been using end mills instead of router bits for years, and have came to the same conclusion as you did- they are MUCH better for mortising. I typically use TiN coated HSS bits because of their incredibly cheap cost, and thus, disposability. However, I run these bits at the slowest setting of my 625, ~10,000 rpm I think, and have had no problems. You’re also correct that info for machining metal is everywhere, and wood not; so w/ that in mind, I decided to generally follow the guidelines for softer metals like brass and aluminum for wood. If you think about it, a lot of exotics are actually more difficult to machine than these metals- cocobolo, ebony, and bubinga come to mind.

Thanks for a great blog, and keep up the great work!

Thanks for the comment, Rob!

I searched without success for information on machining wood with end mills. I’ve read about SFMs up to 1200 for aluminum and plastics, which translate to about 12,000 RPM for a 3/8″ bit and 18,000 RPM for a 1/4″ bit. However, it is hard to draw inferences from this regarding mortising wood. Chip congestion may be worse with these materials than most woods, I don’t know. Also, feed rate, type of cut, depth of cut per pass, and the type of machine (CNC, hand-held router, etc) are all important variables.

So I’ve based my assessment on how the router feels and sounds as I cut, chip clearance, and especially on results such as pictured above: a 3/8″ mortise, 1 1/2″ deep, in bubinga, routed with a template guide in a slot jig at 20,000 RPM. No burning or straining, and a clean, true mortise. Maybe I’ll try experimenting with dropping the RPMs a bit just to see how it goes.

Happy woodworking, Rob.

Rob

I forgot to mention, my speed is based partly on the fact that I use HSS end mills, not carbide. Could be you’re getting better results at higher rpm’s because of that, I’m not sure. As w/ anything else though, go w/ what works best for YOU. I was just adding my 2 cents to the equation. :-)

Thanks Rob, I appreciate your input.

Rob

Hi Rob,

As usual, a well written and useful entry. It is interesting to me to read your pieces because I am at the point in my small shop work where focusing on small refinements is the order of the day, and you have mentioned many of them in your blog.

The morticing jig for plunge routers that Tage Frid described in his technique book has served me very well, but quality slot morticers have always been in the back of my mind as machines that might be a subtantial step up in quality, eliminating that last bit of vibration and error introduced by a hand held and controlled tool such as the plunge router. Are end mills used in those machines? Have you ever used one?

Best,

Tico

Hi Tico,

Thanks for the comment. I am glad you find the posts useful.

I have not used a slot mortiser. The current issue (#206) of Fine Woodworking has a nice review of mortising methods. My go-to method is the plunge router with a template guide that rides in a slot jig. These have all been shop-made jigs, but lately I’m finding the Mortise Pal to be handy. I truly get virtually no vibration or error with this method – unless, of course, I make a mistake (and that happens more than I should admit.)

Rob

Well, I havn’t done much wood working yet, but I’ve milled lots of steel. My google search today was to discover why endmills are not typically used in woodworking. This article convinces me there is no good reason other than marketing and the typical woodworker’s lack of exposure to metalworking tools. I wanted to coment on the previously mentioned speed concern with endmills…..the only speed limitation is due to heat. Modern cnc machining centers (for milling metal) have spindle speeds upwards of 20,000 rpm. It is the surface speed at the circumference of the tool and the resulting heat generated that becomes the limiting factor…..smaller tool can run infinitly faster than a large one. This probably isn’t as much of a concern with wood. I imagine the wood will burn before harming the carbide cutter. HSS endmills would probably need to be run an order of magnitude slower [than carbide] to prevent their demise.

Thanks for the information, Jeff. It’s helpful to hear from someone with your background.

I haven’t had problems with burning the wood but I cut the mortise in shallow steps and I clear out the chips regularly. For making a 3/8″ mortise in a dense wood like bubinga, I’ll take probably about 10 passes to cut a 1 1/4″ deep mortise. I listen and feel for signs of strain from the bit or router, but it goes nice and smoothly.

Rob

Great thread; very informative. Thanks.

Fred

first, I enjoy your postings. Well written. I don’t often take the time to read woodworking blogs but I look forward to yours.

I searched the manufacturers for end mills but the selection is so confusing I have no idea which ones to order. Can you be more specific on which ones you use?

Peter

Hi Peter,

Thank you for the kind words and for reading.

The end mills that I have found work well are classified as:

Single, Standard, Center-cutting, Uncoated, Four-flute, Solid carbide, Plain shank, 30-degree helix.

An example is item #85315240, a 3/8 diameter end mill, from MSC Industrial Supply.

http://www1.mscdirect.com/cgi/nnsrhm

Click on End Mills, etc in the Big Book Index pages on the left. Then Single End Mills in section 3, then Standard.

In the drop-down lists, select Four-flute, Solid Carbide.

THEN put in the size parameters: cut diameter, shank diameter, overall length, and cutting length.

Now you’ve got 1-2 dozen bits to examine. You are looking for center-cutting and uncoated (coating is OK but not necessary for wood and costs more). I would avoid selecting brand, type, and coating from the drop-down lists because you may exclude some bits that you will want to consider. Just look over the list and look for center-cutting and uncoated.

This is what works for me.

Rob

Very useful information. Thank you for your writing.

Sorry for being ignorant, what am I missing here? I have collets for 1/4″ and 1/2″. How do I put a 3/8″ mill end in my router? Thanks! Jeff Jones, Battle Ground, WA

No problem, Jeff! To chuck the 3/8″ shank in your router, you have two options.

For many routers, including the DW 625, a 3/8″ collet is available. That is the best option.

An alternative [and there is no other choice that I am aware of for 5/16″ (8mm) end mills] is to use a collet reducer. This is a sleeve which fits into your 1/2″ collet and fills the gap for the smaller shank bit.

The disadvantage of a collet reducer is that it introduces more stiffness to the collet assembly and therefore the chuck needs to be tightened very snugly to keep a good grip on the bit. The better collet reducers are more flexible.

Infinity Tools sells reducers with six grooves in the wall for flexibility:

http://www.infinitytools.com/3_8-Router-Collet-Reducing-Sleeve/productinfo/SLV-003/

Whiteside also makes reducers, available directly from them or from Woodcraft:

http://www.woodcraft.com/Product/2008167/9245/12-to-38-Router-Bit-Shank-Adapter-Whiteside-6402.aspx

Lee Valley also sells reducers, but note that the 1/2-3/8 reducer has only one split and is therefore rather stiff. It also has no lip, so it inconveniently tends to slide too far into the main router collet.

http://www.leevalley.com/US/wood/page.aspx?p=30126&cat=1,46168,46180

Good luck with your mortising. Take small depth increments, and listen and feel for signs of cutting stress.

Rob