1. Be a control freak

Once a machine woodworking procedure starts, any unexpected event will occur suddenly, probably too quickly for you to react. At that point, your defense is whatever margins of safety, such as guards and hand clearances, that have been built into the setup and come into play after the mishap. You have to hope they are adequate to prevent injury.

The safest way to use a woodworking machine is to know, before starting, exactly what is about to happen. It should be a completely predictable operation. We know the machine itself will operate in a fully predictable manner (the blade or bit spins), and so your job is to thoroughly understand and control the interactions among you, the wood, and the machine. You must understand all the forces at work. In short, don’t hit the start switch if your mind harbors doubts!

Of course, still use the guards and clearances.

2. Cut or throw?

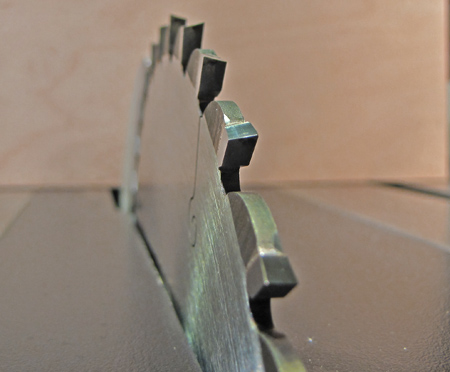

A machine blade or cutter, given the opportunity, will always throw the wood rather than cut it. You must deny the machine that opportunity by restricting the movement of the wood, and ensure that it has the capacity to cut the wood. Using hand-held power tools, it may be the tool itself, with your hands still holding it, that gets kicked.

All of the following mishaps, among many more, are essentially a cutter throwing the work piece because the operator gave the machine an alternative to cutting it:

- Table saw kickback – the absence of a splitter/riving knife allows the kerf to pinch the rising blade which grips and violently throws the wood.

- Thickness planer kickback – a short board is freed from the infeed roller before reaching the outfeed roller so the blades grab and eject the unrestricted wood.

- Drill press – the rim of a bit, such as a large diameter Forstner, snags an unclamped work piece and throws it, or worse, pulls in the hand that is trying to hold it. Re-entering a hole with a spinning bit increases the chance of this disaster.

- Bandsaw – wood held above the table surface is presented to a coarse tooth blade and gets slammed to the table, drawing the worker’s hands with it, possibly into the blade.

- Router table – uncontrolled climb cutting (feeding the work piece in the direction of the cutting edge rotation) zooms the wood across the table, possibly carrying the woodworker’s hands into the cutter.

Well, I’m getting uneasy just writing these scenarios. Of course, these two concepts are just part of safe practice, and there are many more ways to get hurt with machines. However, keeping these two basic principles in mind – and in action – will go a long way toward using machines safely.

Stay safe in the shop!

Great reminders! I recently had an unexpected bit of drama with a drum sander. I’d bartered for it from a fellow woodworker and assumed it had been set up properly. On my first test pass it shot my workpiece out like it was a baseball pitching machine. I’ve left the piece in the wall as a reminder.

It’s that climb cutting a small piece w/ a router/shaper table that unnerves the control freak in me,

Chris,

Whew!

Kurt,

I’d hold the piece with a handscrew or jig. I don’t want to take chances!

Thanks for the comments,

Rob